Benchmarking your Model

This chapter explores methods for comparing the performance of different models applied to complex problems, where the basic model leaves room for improvement — either in runtime or in solution quality, especially when the model cannot always be solved to optimality. As a scientist writing a paper on a new model (or, more likely, a new algorithm that internally uses a model), this will be the default case as research on a problem that can already be solved well is hard to publish. Whether you aim merely to evaluate whether your new approach outperforms the current one or intend to prepare a formal scientific publication, you face the same challenges; in the latter case, however, the process becomes more extensive and formalized (but this may also be true for the first case depending on your manager).

In some cases, the primary performance bottleneck may not lie within CP-SAT

itself but rather in the Python code used to generate the model.

Identifying the most resource-intensive segments of your Python code is

therefore essential. The profiler

Scalene has proven to be

particularly effective for pinpointing such issues. In many situations, simple

logging statements (e.g.,

|

During the explorative phase, when you probe different ideas, you will likely select one to five instances that you can run quickly and compare. However, for most applications, this number is insufficient, and you risk overfitting your model to these instances — gaining performance improvements on them but sacrificing performance on others. You may even limit your model’s ability to solve certain instances.

A classic example involves deactivating specific CP-SAT search strategies or preprocessing steps that have not yielded benefits on the selected instances. If your instance set is large enough, the risk is low; however, if you have only a few instances, you may remove the single strategy necessary to solve a particular class of problems. Modern solvers include features that impose a modest overhead on simple instances but enable solving otherwise intractable cases. This trade-off is worthwhile: do not sacrifice the ability to solve complex instances for a marginal performance gain on simple ones. Therefore, always benchmark your changes properly before deploying them to production, even if you do not plan to publish your results scientifically.

Note that this chapter focuses solely on improving the performance of your model with respect to its specific formulation; it does not address the evaluation of the model’s accuracy or its business value. When tackling a real-world problem, where your model is merely an approximation of reality, it is essential to also consider refining the approximation and monitoring the real-world performance of the resulting solutions. In some cases, simpler formulations not only yield better outcomes but are also easier to optimize for.

No-Free-Lunch Theorem and Timeouts

The no‐free‐lunch theorem and timeouts complicate benchmarking more than you might have anticipated. The no‐free‐lunch theorem asserts that no single algorithm outperforms all others across every instance, which is especially true for NP‐hard problems. Consequently, improving performance on some instances often coincides with degradations on others. It is essential to assess whether the gains justify the losses.

Another challenge arises when imposing a time limit to prevent individual instances from running indefinitely. Without such a limit, benchmark runs can become prohibitively long. However, including aborted runs in the dataset complicates performance evaluation, as it remains unclear whether a solver would have found a solution shortly after the timeout or was trapped in an infinite loop. Discarding all instances that timed out on a particular model restricts the evaluation to simpler instances, even though the more complex ones are often of greater interest. Conversely, discarding all models that timed out on any instance may leave no viable candidates, as any solver is likely to fail on at least one instance in a sufficiently large benchmark set. Whether the goal is to find a provably optimal solution, the best solution within a fixed time limit, or simply any feasible solution, it is essential to enable comparisons over data sets that include unknown outcomes.

Example: Nurse Rostering Problem Benchmark

Let us examine the performance of CP-SAT, Gurobi, and Hexaly on a Nurse Rostering Problem to illustrate the additional challenge of selecting an appropriate time limit. Nurse rostering is a complex yet common problem in which nurses must be assigned to shifts while satisfying a variety of constraints. Since CP-SAT, Gurobi, and Hexaly differ significantly in their underlying algorithms, the comparison reveals pronounced performance differences. However, such patterns can also be observed when using the same solver across instances, albeit usually not as pronounced.

The following two plots illustrate the value of the incumbent solution (i.e., the best solution found so far) and the best proven lower bound during the search. These are challenging instances, and only Gurobi is able to find an optimal solution.

Notably, the best-performing solver changes depending on the allotted computation time. For this problem, Hexaly excels at finding good initial solutions quickly but tends to stall thereafter. CP-SAT requires slightly more time to get started but demonstrates steady progress. In contrast, Gurobi begins slowly but eventually makes substantial improvements.

So, which solver is best for this problem?

|

|---|

| Performance comparison of CP-SAT, Gurobi, and Hexaly on instance 19 of the Nurse Rostering Problem Benchmark. Hexaly starts strong but is eventually overtaken by CP-SAT. Gurobi surpasses Hexaly near the end by a small margin. CP-SAT and Gurobi converge to nearly the same lower bound. |

|

|---|

| Performance comparison of CP-SAT, Gurobi, and Hexaly on instance 20 of the Nurse Rostering Problem Benchmark. Hexaly again performs well early but is outperformed by CP-SAT. Gurobi maintains a poor incumbent value for most of the runtime but eventually makes a significant improvement and proves optimality. The optimal solution is visibly superior to CP-SAT’s best solution. CP-SAT is unable to prove a meaningful lower bound for this instance. |

These two plots (and even this specific problem) are insufficient to draw definitive conclusions about the overall performance of the solvers. Nevertheless, it is remarkable that our beloved open-source solver, CP-SAT, performs so well against the commercial solvers Gurobi and Hexaly in this context. |

If provably optimal solutions are required, Gurobi may be the most suitable choice; however, the likelihood of achieving optimality is low for most instances. If your instances are expected to grow in size and require fast solutions, Hexaly might be preferable, as it appears highly effective at finding good solutions quickly. This observation is also supported by preliminary results on larger instances, for which neither CP-SAT nor Gurobi find any feasible solution. CP-SAT, by contrast, offers a strong compromise between the two: although it starts more slowly, it maintains consistent progress throughout the search.

A commonly used metric for convergence is the primal integral, which measures the area under the curve of the incumbent solution value over time. It provides a single scalar that summarizes how quickly a solver improves its best-known solution. CP-SAT reports a related metric: the integral of the logarithm of the optimality gap, which also accounts for the quality of the bound. These metrics offer an objective measure of solver progress over time, though they may not fully capture problem-specific or subjective priorities. |

Defining Your Benchmarking Goals

The first step is to determine your specific requirements and how best to measure solver performance accordingly. It is not feasible to manually plot performance for every instance and assign scores based on subjective impressions; such an approach does not scale and lacks objectivity and reproducibility. Instead, you should define a concrete metric that accurately reflects your goals. One strategy is to carefully select benchmark instances that are still likely to be solved to optimality, with the expectation that performance trends will generalize to larger instances. Another to decide for a fixed time limit we are willing to wait for a solution, and then measure how well each solver performs under these constraints. While no evaluation method will be perfect, it is essential to remain aware of potential threats to the validity of your results. Let us go through some common scenarios.

Empirical studies on algorithms have historically faced some tension within the academic community, where theoretical results are often viewed as more prestigious or fundamental. The paper Needed: An Empirical Science of Algorithms by John Hooker (1994) offers a valuable historical and philosophical perspective on this issue. |

Common Benchmarking Scenarios and Visualization Techniques

Several common benchmarking scenarios arise in practice. To select an appropriate visualization or evaluation method, it is important to first identify which scenario applies to your case and to recognize which tools are better suited for other contexts. Avoid choosing the most visually appealing or complex plot by default; instead, select the one that best serves your analytical goals. Keep in mind that the primary purpose of a plot is to make tabular data more accessible and easier to interpret. It does not replace the underlying tables, nor does it provide definitive answers.

-

Instances are always solved to optimality, and only runtime matters. This is the simplest benchmarking scenario. If every instance can be solved to optimality and your only concern is runtime, you can summarize performance using the mean (relative) runtime or visualize it using a basic box plot. The primary challenge here lies in choosing the appropriate type of mean (e.g., arithmetic, geometric, harmonic) and selecting representative instances that reflect production-like conditions. For this case, the rest of the chapter may be skipped.

-

Optimal or feasible solutions are sought, but may not always be found within the time limit. When timeouts occur, runtimes for unsolved instances become unknown, making traditional means unreliable. In such cases, cactus plots are an effective way to visualize solver performance, even in the presence of incomplete data.

-

The goal is to find the best possible solution within a fixed time limit. Here, the focus is on solution quality under time constraints, rather than on whether optimality is reached. Performance plots are especially suitable for this purpose, as they reveal how closely each solver or model approaches the best-known solution across the benchmark set.

-

Scalability analysis: how performance evolves with instance size. If you are analyzing how well a model scales, i.e., how large an instance it can solve to optimality and how the optimality gap grows thereafter, split plots are a good choice. They show runtime for solved instances and optimality gap for those that exceed the time limit, allowing for a unified view of scalability.

-

Multi-metric performance comparison against a baseline. When you want a quick, intuitive overview of how your model performs across several metrics, such as runtime, objective value, and lower bound, scatter plots with performance zones are ideal. They provide a clear comparative visualization, making it easy to spot outliers and trade-offs across dimensions.

Use the SIGPLAN Empirical Evaluation Checklist if your evaluation has to satisfy academic standards. |

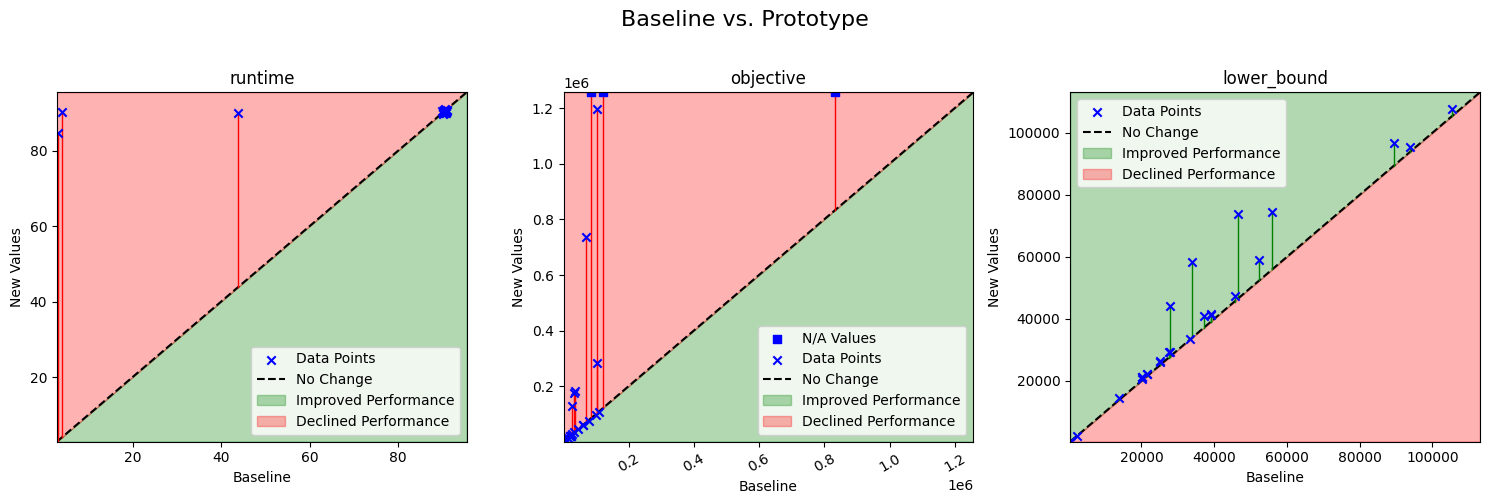

Quickly Comparing to a Baseline Using Scatter Plots

Scatter plots with performance zones are, in my experience, highly effective for

quickly comparing the performance of a prototype against a baseline across

multiple metrics. While these plots do not provide a formal quantitative

evaluation, they offer a clear visual overview of how performance has shifted.

Their key advantages are their intuitive readability and their ability to

accommodate NaN values. They are particularly useful for identifying outliers,

though they can be less effective when too many points overlap or when data

ranges vary significantly (sometimes, a log scale can help here).

Consider the following example table, which compares a basic optimization model

with a prototype model in terms of runtime, objective value, and lower bound.

The runtime is capped at 90 seconds, and if no optimal solution is found within

this limit, the objective value is set to NaN. A run only terminates before

the time limit if an optimal solution is found.

Example Data

| instance_name | strategy | runtime | objective | lower_bound |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| att48 | Prototype | 89.8327 | 33522 | 33522 |

| att48 | Baseline | 90.1308 | 33522 | 33369 |

| eil101 | Prototype | 90.0948 | 629 | 629 |

| eil101 | Baseline | 43.8567 | 629 | 629 |

| eil51 | Prototype | 84.8225 | 426 | 426 |

| eil51 | Baseline | 3.05334 | 426 | 426 |

| eil76 | Prototype | 90.2696 | 538 | 538 |

| eil76 | Baseline | 4.09839 | 538 | 538 |

| gil262 | Prototype | 90.3314 | 13817 | 2368 |

| gil262 | Baseline | 90.8782 | 3141 | 2240 |

| kroA100 | Prototype | 90.5127 | 21282 | 21282 |

| kroA100 | Baseline | 90.0241 | 22037 | 20269 |

| kroA150 | Prototype | 90.531 | 27249 | 26420 |

| kroA150 | Baseline | 90.3025 | 27777 | 24958 |

| kroA200 | Prototype | 90.0019 | 176678 | 29205 |

| kroA200 | Baseline | 90.7658 | 32749 | 27467 |

| kroB100 | Prototype | 90.1334 | 22141 | 22141 |

| kroB100 | Baseline | 90.5845 | 22729 | 21520 |

| kroB150 | Prototype | 90.7107 | 128751 | 26016 |

| kroB150 | Baseline | 90.9659 | 26891 | 25142 |

| kroB200 | Prototype | 90.7931 | 183078 | 29334 |

| kroB200 | Baseline | 90.3594 | 34481 | 27708 |

| kroC100 | Prototype | 90.5131 | 20749 | 20749 |

| kroC100 | Baseline | 90.3035 | 21118 | 20125 |

| kroD100 | Prototype | 90.0728 | 21294 | 21294 |

| kroD100 | Baseline | 90.2563 | 21294 | 20267 |

| kroE100 | Prototype | 90.4515 | 22068 | 22053 |

| kroE100 | Baseline | 90.6112 | 22341 | 21626 |

| lin105 | Prototype | 90.4714 | 14379 | 14379 |

| lin105 | Baseline | 90.6532 | 14379 | 13955 |

| lin318 | Prototype | 90.8489 | 282458 | 41384 |

| lin318 | Baseline | 90.5955 | 103190 | 39016 |

| linhp318 | Prototype | 90.9566 | nan | 41412 |

| linhp318 | Baseline | 90.7038 | 84918 | 39016 |

| pr107 | Prototype | 90.3708 | 44303 | 44303 |

| pr107 | Baseline | 90.4465 | 45114 | 27784 |

| pr124 | Prototype | 90.1689 | 59167 | 58879 |

| pr124 | Baseline | 90.8673 | 60760 | 52392 |

| pr136 | Prototype | 90.0296 | 96781 | 96772 |

| pr136 | Baseline | 90.2636 | 98850 | 89369 |

| pr144 | Prototype | 90.3141 | 58537 | 58492 |

| pr144 | Baseline | 90.6465 | 59167 | 33809 |

| pr152 | Prototype | 90.4742 | 73682 | 73682 |

| pr152 | Baseline | 90.8629 | 79325 | 46604 |

| pr226 | Prototype | 90.1845 | 1.19724e+06 | 74474 |

| pr226 | Baseline | 90.6676 | 103271 | 55998 |

| pr264 | Prototype | 90.4012 | 736226 | 41020 |

| pr264 | Baseline | 90.9642 | 68802 | 37175 |

| pr299 | Prototype | 90.3325 | nan | 47375 |

| pr299 | Baseline | 90.19 | 120489 | 45594 |

| pr439 | Prototype | 90.5761 | nan | 95411 |

| pr439 | Baseline | 90.459 | 834126 | 93868 |

| pr76 | Prototype | 90.2718 | 108159 | 107727 |

| pr76 | Baseline | 90.2951 | 110331 | 105340 |

| st70 | Prototype | 90.2824 | 675 | 675 |

| st70 | Baseline | 90.1484 | 675 | 663 |

From the table, we can already spot some fundamental issues. For example, the prototype fails on three instances, and several instances yield significantly worse results than the baseline. However, when we turn to the scatter plots with performance zones, such anomalies become immediately apparent.

|

|---|

| Scatter plot comparing the performance of a prototype model against a baseline model across three metrics: runtime, objective value, and lower bound. The x-axis represents the baseline model’s performance; the y-axis shows the prototype model’s performance. Color-coded zones indicate relative performance levels, making it easier to identify where the prototype outperforms or underperforms the baseline. |

For runtime, both models typically hit the time limit, so there is limited variation to observe. However, the baseline model solves a few instances significantly faster, whereas the prototype consistently uses the full time limit. For the objective value, both models produce similar results on most instances. Yet, particularly on the larger instances, the prototype yields either very poor or no solutions at all.

Interestingly, the lower bounds produced by the prototype are much better for some instances. This improvement was not obvious from a cursory review of the table but becomes immediately noticeable in the plots.

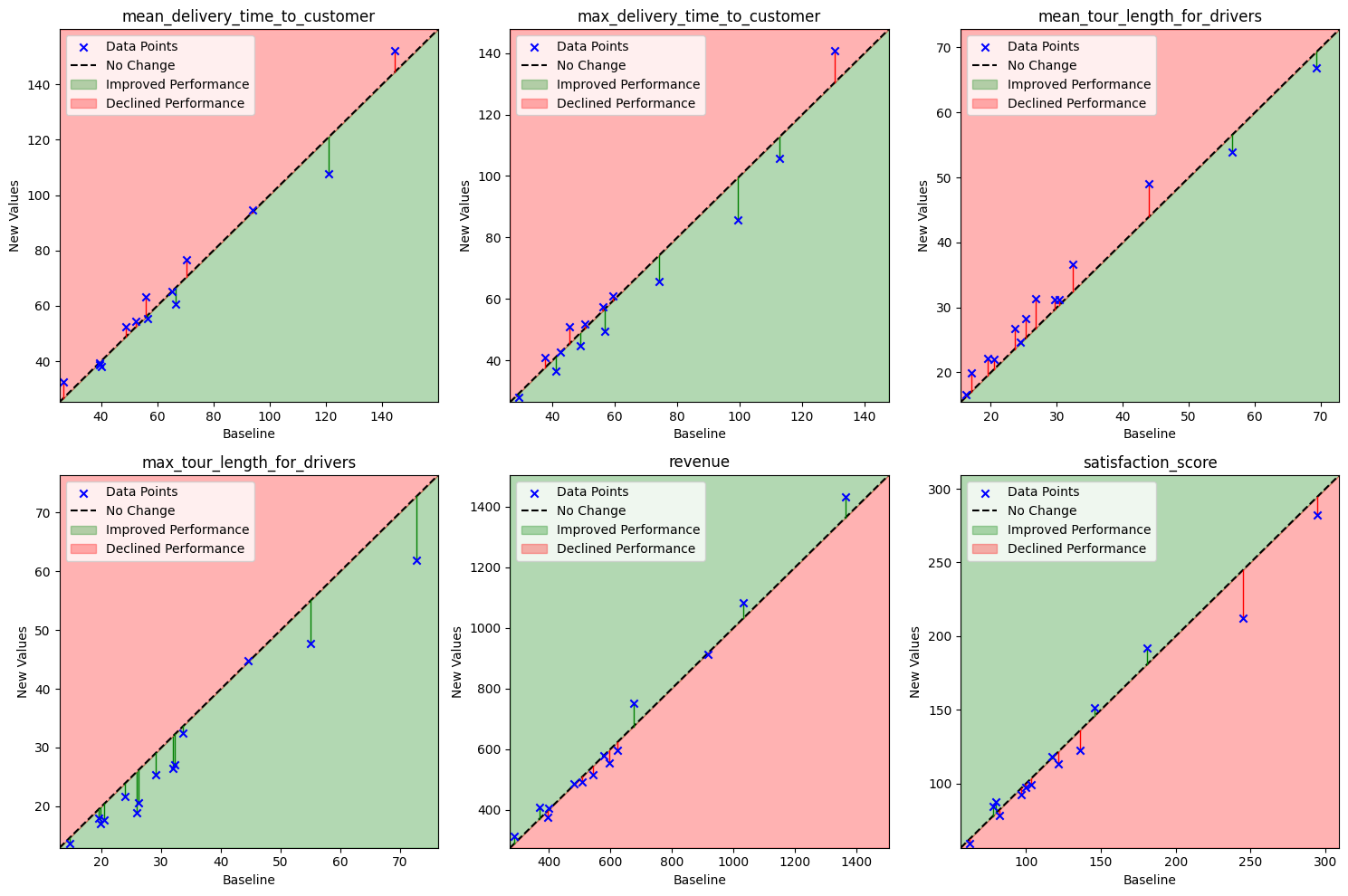

Scatter plots are also highly effective when working with multiple performance metrics, particularly when you want to ensure that gains in one metric do not come at the expense of unacceptable losses in another. In practice, it is often difficult to precisely quantify the relative importance of each metric from the outset. The intuitive nature of these plots offers a valuable overview, serving as a visual aid before you commit to a specific performance metric. The example below illustrates a hypothetical scenario involving a vehicle routing problem.

|

|---|

| Scatter plots illustrating performance trade-offs across multiple metrics in a hypothetical vehicle routing problem. These plots help assess whether improvements in one metric come at the cost of significant regressions in another. Their intuitive layout makes them especially useful when metric priorities are not yet clearly defined, offering a quick overview of relative performance and highlighting outliers across different algorithm versions. |

Here is the code I used to generate the plots. You can freely copy and use it.

"""

This module contains functions to plot a scatter comparison of baseline and new values with performance areas highlighted.

You can freely use and distribute this code under the MIT license.

Changelog:

2024-08-27: First version

2024-08-29: Added lines to the diagonal to help with reading the plot

2025-06-07: Basic improvements and fixing issue with index comparison.

(c) 2025 Dominik Krupke, https://github.com/d-krupke/cpsat-primer

"""

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

def plot_performance_scatter(

ax,

baseline: pd.Series,

new_values: pd.Series,

lower_is_better: bool = True,

title: str = "",

**kwargs,

):

"""

Plot a scatter comparison of baseline and new values with performance areas highlighted.

Parameters:

ax (matplotlib.axes.Axes): The axes on which to plot.

baseline (pd.Series): Series of baseline values.

new_values (pd.Series): Series of new values.

lower_is_better (bool): If True, lower values indicate better performance.

title (str): Title of the plot.

**kwargs: Additional keyword arguments for customization (e.g., 'color', 'marker').

"""

if not isinstance(baseline, pd.Series) or not isinstance(new_values, pd.Series):

raise ValueError("Both baseline and new_values should be pandas Series.")

if baseline.size != new_values.size:

raise ValueError("Both Series should have the same length.")

scatter_kwargs = {

"color": kwargs.get("color", "blue"),

"marker": kwargs.get("marker", "x"),

"label": kwargs.get("label", "Data Points"),

}

line_kwargs = {

"color": kwargs.get("line_color", "k"),

"linestyle": kwargs.get("line_style", "--"),

"label": kwargs.get("line_label", "No Change"),

}

fill_improve_kwargs = {

"color": kwargs.get("improve_color", "green"),

"alpha": kwargs.get("improve_alpha", 0.3),

"label": kwargs.get("improve_label", "Improved Performance"),

}

fill_decline_kwargs = {

"color": kwargs.get("decline_color", "red"),

"alpha": kwargs.get("decline_alpha", 0.3),

"label": kwargs.get("decline_label", "Declined Performance"),

}

# Replace inf values with NaN

baseline = baseline.replace([np.inf, -np.inf], np.nan)

new_values = new_values.replace([np.inf, -np.inf], np.nan)

max_val = max(baseline.max(skipna=True), new_values.max(skipna=True)) * 1.05

min_val = min(baseline.min(skipna=True), new_values.min(skipna=True)) * 0.95

# get indices of NA values

na_indices = baseline.isna() | new_values.isna()

if lower_is_better:

# replace NA values with max_val

baseline = baseline.fillna(max_val)

new_values = new_values.fillna(max_val)

else:

# replace NA values with min_val

baseline = baseline.fillna(min_val)

new_values = new_values.fillna(min_val)

# plot the na_indices with a different marker

if na_indices.any():

ax.scatter(

baseline[na_indices],

new_values[na_indices],

marker="s",

color=scatter_kwargs["color"],

label="N/A Values",

zorder=2,

)

# add the rest of the data points

ax.scatter(

baseline[~na_indices], new_values[~na_indices], **scatter_kwargs, zorder=2

)

ax.plot([min_val, max_val], [min_val, max_val], zorder=1, **line_kwargs)

x = np.linspace(min_val, max_val, 500)

if lower_is_better:

ax.fill_between(x, min_val, x, zorder=0, **fill_improve_kwargs)

ax.fill_between(x, x, max_val, zorder=0, **fill_decline_kwargs)

else:

ax.fill_between(x, x, max_val, zorder=0, **fill_improve_kwargs)

ax.fill_between(x, min_val, x, zorder=0, **fill_decline_kwargs)

# draw thin lines to the diagonal to help with reading the plot.

# A problem without lines is that one tends to use the distance

# to the diagonal as a measure of performance, which is not correct.

# Instead, it is `y-x` that should be used.

for old_val, new_val in zip(baseline, new_values):

if pd.isna(old_val) and pd.isna(new_val):

continue

if pd.isna(old_val):

old_val = min_val if lower_is_better else max_val

if pd.isna(new_val):

new_val = min_val if lower_is_better else max_val

if lower_is_better and new_val < old_val:

ax.plot(

[old_val, old_val],

[old_val, new_val],

color="green",

linewidth=1.0,

zorder=1,

)

elif not lower_is_better and new_val > old_val:

ax.plot(

[old_val, old_val],

[old_val, new_val],

color="green",

linewidth=1.0,

zorder=1,

)

elif lower_is_better and new_val > old_val:

ax.plot(

[old_val, old_val],

[old_val, new_val],

color="red",

linewidth=1.0,

zorder=1,

)

elif not lower_is_better and new_val < old_val:

ax.plot(

[old_val, old_val],

[old_val, new_val],

color="red",

linewidth=1.0,

zorder=1,

)

ax.set_xlim(min_val, max_val)

ax.set_ylim(min_val, max_val)

ax.set_xlabel(kwargs.get("xlabel", "Baseline"))

ax.set_ylabel(kwargs.get("ylabel", "New Values"))

if title:

ax.set_title(title)

ax.legend()

def plot_comparison_grid(

baseline_data: pd.DataFrame,

new_data: pd.DataFrame,

metrics: list[tuple[str, str]],

n_cols: int = 4,

figsize: tuple[int, int] | None = None,

suptitle: str = "",

subplot_kwargs: dict | None = None,

**kwargs,

):

"""

Plot a grid of performance comparisons for multiple metrics.

Parameters:

baseline_data (pd.DataFrame): DataFrame containing the baseline data.

new_data (pd.DataFrame): DataFrame containing the new data.

metrics (list of tuple of str): List of tuples containing column names and comparison direction ('min' or 'max').

n_cols (int): Number of columns in the grid.

figsize (tuple of int): Figure size (width, height).

suptitle (str): Title for the entire figure.

**kwargs: Additional keyword arguments to pass to individual plot functions.

Returns:

fig (matplotlib.figure.Figure): The figure object containing the plots.

axes (np.ndarray): Array of axes objects corresponding to the subplots.

"""

n_metrics = len(metrics)

n_cols = min(n_cols, n_metrics)

n_rows = (n_metrics + n_cols - 1) // n_cols # Ceiling division

# Validate columns and directions

for column, direction in metrics:

if direction not in {"min", "max"}:

raise ValueError("The direction should be either 'min' or 'max'.")

if column not in baseline_data.columns or column not in new_data.columns:

raise ValueError(f"Column '{column}' not found in the data.")

# Validate index alignment

if set(baseline_data.index) != set(new_data.index):

raise ValueError("Indices of the DataFrames do not match (different values).")

if figsize is None:

figsize = (5 * n_cols, 5 * n_rows)

fig, axes = plt.subplots(n_rows, n_cols, figsize=figsize)

axes = axes.flatten()

for ax, (column_name, direction) in zip(axes, metrics):

# Merge kwargs and subplot_kwargs[column_name] (if present) into a new dict

merged_kwargs = dict(kwargs)

if subplot_kwargs and column_name in subplot_kwargs:

merged_kwargs.update(subplot_kwargs[column_name])

plot_performance_scatter(

ax,

baseline_data[column_name],

new_data[column_name],

lower_is_better=(direction == "min"),

title=column_name,

**merged_kwargs,

)

# Turn off any unused subplots

for ax in axes[n_metrics:]:

ax.axis("off")

if suptitle:

fig.suptitle(suptitle, fontsize=16)

plt.tight_layout(rect=[0, 0, 1, 0.96])

return fig, axes

Success-Based Benchmarking: Cactus Plots and PAR Metrics

The SAT community frequently uses cactus plots (also known as survival plots) to effectively compare the time to success of different solvers on a benchmark set, even when timeouts occur. If you are dealing with a pure constraint satisfaction problem, this approach is directly applicable. However, it can also be extended to other binary success indicators — such as proving optimality, even under optimality tolerances.

Additionally, the PAR10 metric is commonly used to summarize solver performance on a benchmark set. It is defined as the average time a solver takes to solve an instance, where unsolved instances (within the time limit) are penalized by assigning them a runtime equal to 10 times the cutoff. Variants like PAR2, which use a penalty factor of 2 instead of 10, are also encountered. While a factor of 10 is conventional, it remains an arbitrary choice. Ultimately, you must decide how to handle unknowns (instances not solved within the time limit) since you only know that their actual runtime exceeds the cutoff. If an explicit performance metric is required to declare a winner, PAR-style metrics are widely accepted but come with notable limitations.

To gain a more nuanced view of solver performance, cactus plots are often employed. In these plots, each solver is represented by a line where each point \( (x, y) \) indicates that \( y \) benchmark instances were solved within \( x \) seconds (there exists also the reversed version).

|

|---|

| Each point \( (x, y) \) shows that \( x \) instances were solved within \( y \) seconds. |

The mean PAR10 scores for the four strategies in the example above are as follows:

| Strategy | PAR10 |

|---|---|

| AddCircuit | 512.133506 |

| Dantzig (Gurobi) | 66.452202 |

| Iterative Dantzig | 752.412118 |

| Miller-Tucker-Zemlin | 1150.014846 |

In case you are wondering, this is some data on solving the Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP) with different strategies. Gurobi dominates, but it is well-known that Gurobi is excellent at solving TSP.

If the number of solvers or models under comparison is not too large, you can also use a variation of the cactus plot to show solver performance under different optimality tolerances. This allows you to examine how much performance improves when the tolerance is relaxed. However, if your primary interest lies in solution quality, performance plots are likely to be more appropriate.

In the following example, different optimality tolerances reveal a visible

performance improvement for the strategies AddCircuit and

Miller-Tucker-Zemlin. For the other two strategies, the impact of tolerance

changes is minimal. This variation of the cactus plot can also be applied to

compare solver performance across different benchmark sets, especially if you

suspect significant variation across instance categories.

|

|---|

| Each line style represents an optimality tolerance. The plot shows how many instances (\( y \)) can be solved within a given time limit (\( x \)) for each tolerance. |

It is also common practice to include a virtual best line in the cactus plot. This line indicates, for each instance, the best time achieved by any solver. Although it does not represent an actual solver, it serves as a valuable reference to evaluate the potential for solver complementarity. If one solver clearly dominates, the virtual best line will coincide with its curve. However, if the lines diverge, it suggests that no single solver is universally superior—a case of the “no free lunch” principle. Even if one solver performs best on 90% of instances, the remaining 10% may be better handled by alternatives. The greater the gap between the best actual solver and the virtual best, the stronger the case for a portfolio approach.

A more detailed discussion on this type of plot can be found in the referenced academic paper: Benchmarking Solvers, SAT-style by Brain, Davenport, and Griggio |

Performance Plots for Solution Quality within a Time Limit

When dealing with instances that typically cannot be solved to optimality, performance plots are often more appropriate than cactus plots. These plots illustrate the relative performance of different models or solvers on a set of instances, usually under a fixed time limit. At the leftmost point of the plot (where \( x = 1 \)), each solver’s line indicates the proportion of instances for which it achieved the best-known solution (not necessarily exclusively). Then its \( (x,y) \) coordinates indicate the proportion \( y \) of instances for which the solver achieved a solution that is at most \( x \) times worse than the best known solution. For example, if a solver has a point at \( (1.05, 0.8) \), it means that it found a solution within 5% of the best-known solution for 80% of the instances. Often, a logarithmic scale is used for the x-axis, especially when the performance ratios vary widely. However, down below we use a linear scale because the values are close to 1.

In the example below, based on the Capacitated Vehicle Routing Problem (CVRP), the performance plots compare three different models across a benchmark set. These plots offer a clear visual summary of how closely each model approaches the best solution.

|

|---|

Performance plot comparing the objective values of different CVRP models on a benchmark set. The Miller–Tucker–Zemlin model performs best on most instances and remains close to the best on the rest. The other two models find the best solution in only about 10% of instances but solve roughly 70% within 2% of the best known solution, with multiple_circuit showing a slight advantage. |

This can of course also be done for the lower bounds produced by each model.

|

|---|

Performance plot comparing the lower bounds produced by each CVRP model. The add_circuit model consistently achieves the best bounds, while the other two models yield bounds that are up to 20% worse in the best case and up to 100% worse (i.e., half the quality) on some instances. |

Here is the code I used to generate the plots. You can freely copy and use it.

# MIT License

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from matplotlib.axes import Axes

def plot_performance_profile(

data: pd.DataFrame,

instance_column: str,

strategy_column: str,

metric_column: str,

direction: str,

comparison: str = "relative",

title: str | None = None,

highlight_best: bool = False,

ax: Axes | None = None,

scale: str | None = None,

log_base: int = 2,

figsize: tuple = (9, 6),

) -> Axes:

"""

Plot a performance profile, either on a relative-ratio basis or absolute-difference basis:

- For comparison="relative":

x-axis: performance ratio τ (log scale if τ_max > 10)

τ = (value / best) if direction="min", or τ = (best / value) if direction="max".

- For comparison="absolute":

x-axis: absolute difference Δ = (value - best) if direction="min",

or Δ = (best - value) if direction="max".

- y-axis: proportion of problems with τ (or Δ) ≤ x for each solver.

- If highlight_best=True, detect and bold the dominating solver curve (AUC in appropriate space).

- Ensures a reasonable number of ticks on the x-axis.

Args:

data: DataFrame with columns [instance, strategy, metric].

instance_column: column name identifying each problem instance.

strategy_column: column name identifying each solver/strategy.

metric_column: column name of the performance metric (e.g. runtime or cost).

direction: "min" if lower metric → better, "max" if higher → better.

comparison: "relative" or "absolute".

title: Optional plot title.

highlight_best: If True, find the solver with largest AUC and draw it in bold.

ax: An existing matplotlib Axes to draw into. If None, a new Figure+Axes will be created using figsize.

scale: x-axis scale override ("linear" or "log"); if None, chosen automatically.

log_base: base for log scale if used (default 2).

figsize: Tuple (width, height). Only used if ax is None.

Returns:

The matplotlib Axes containing the performance profile.

"""

if direction not in ("min", "max"):

raise ValueError("`direction` must be 'min' or 'max'.")

if comparison not in ("relative", "absolute"):

raise ValueError("`comparison` must be 'relative' or 'absolute'.")

# 1) Compute best value per instance

best_val = data.groupby(instance_column)[metric_column].agg(direction)

# 2) Pivot to get per-instance × per-strategy medians

pivot = (

data.groupby([instance_column, strategy_column])[metric_column]

.median()

.unstack(fill_value=np.nan)

)

# 3) Build comparison matrix C[p, s]

comp = pd.DataFrame(index=pivot.index, columns=pivot.columns, dtype=float)

if comparison == "relative":

for strat in pivot.columns:

if direction == "min":

comp[strat] = pivot[strat] / best_val

else: # direction == "max"

comp[strat] = best_val / pivot[strat]

comp = comp.replace([np.inf, -np.inf, 0.0], np.nan)

else: # comparison == "absolute"

for strat in pivot.columns:

if direction == "min":

comp[strat] = pivot[strat] - best_val

else: # direction == "max"

comp[strat] = best_val - pivot[strat]

comp = comp.replace([np.inf, -np.inf], np.nan)

# 4) Collect all distinct x-values (τ or Δ), including baseline

all_vals = comp.values.flatten()

finite_vals = all_vals[np.isfinite(all_vals)]

baseline = 1.0 if comparison == "relative" else 0.0

all_x = np.unique(np.sort(finite_vals))

all_x = np.concatenate(([baseline], all_x))

all_x = np.unique(np.sort(all_x))

# 5) Build performance-profile DataFrame ρ(x)

n_instances = comp.shape[0]

profile = pd.DataFrame(index=all_x, columns=comp.columns, dtype=float)

for x in all_x:

leq = (comp <= x).sum(axis=0)

profile.loc[x] = leq / n_instances

# 6) Identify dominating solver if requested (max AUC)

best_solver = None

if highlight_best:

if comparison == "relative":

# integrate ρ(τ) w.r.t. log(τ)

log_x = np.log(all_x)

areas = {}

for strat in profile.columns:

y = profile[strat].astype(float).values

areas[strat] = np.trapz(y, x=log_x)

best_solver = max(areas, key=areas.get)

else:

# integrate ρ(Δ) w.r.t. Δ

areas = {}

for strat in profile.columns:

y = profile[strat].astype(float).values

areas[strat] = np.trapz(y, x=all_x)

best_solver = max(areas, key=areas.get)

# 7) Create or use existing Axes

if ax is None:

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=figsize)

else:

fig = ax.figure

# 8) Determine scale if not overridden

if scale is None:

if comparison == "relative" and all_x[-1] > 10:

use_log = True

else:

use_log = False

else:

use_log = scale == "log"

# 9) Plot each solver’s curve

for strat in profile.columns:

y = profile[strat].astype(float)

if highlight_best and strat == best_solver:

ax.step(all_x, y, where="post", label=strat, linewidth=3.0, alpha=1.0)

else:

ax.step(

all_x,

y,

where="post",

label=strat,

linewidth=1.5,

alpha=0.6 if highlight_best else 1.0,

)

# 10) Axis scaling and limits

if comparison == "relative":

if use_log:

ax.set_xscale("log", base=log_base)

ax.set_xlim(all_x[1], all_x[-1] * 1.1)

else:

ax.set_xscale("linear")

ax.set_xlim(1.0, all_x[-1] * 1.1)

xlabel = (

f"Within this factor of the best (log{log_base} scale)"

if use_log

else "Within this factor of the best (linear scale)"

)

else: # absolute

ax.set_xscale("linear")

ax.set_xlim(0.0, all_x[-1] * 1.1)

xlabel = "Absolute difference from the best"

ax.set_ylim(0.0, 1.02)

ax.set_xlabel(xlabel, fontsize=12)

ax.set_ylabel("Proportion of problems", fontsize=12)

if title:

ax.set_title(title, fontsize=14, pad=14)

else:

ax.set_title("Performance Profile", fontsize=14, pad=14)

ax.axvline(x=baseline, color="gray", linestyle="--", alpha=0.7)

ax.grid(True, which="both", linestyle=":", linewidth=0.5)

# 11) Legend inside lower right

ax.legend(loc="lower right", frameon=False)

fig.tight_layout()

return ax

Tangi Migot has written an excellent article on Performance Plots. Also take a look on the original paper Benchmarking optimization software with performance profiles (Dolan & Moré 2002) |

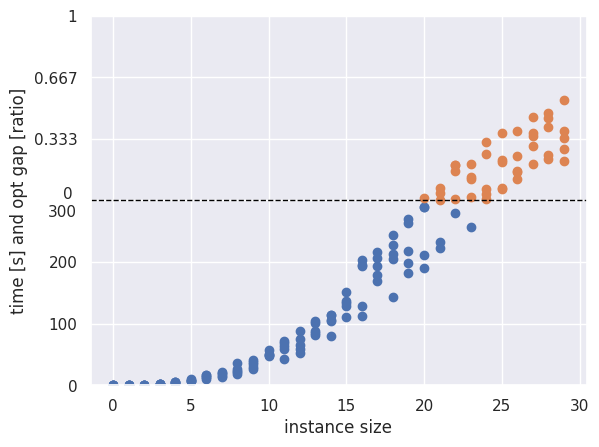

Analyzing the Scalability of a Single Model

When working with a single model and aiming to analyze its scalability, a split plot can serve as an effective visualization. This type of plot shows the model’s runtime across instances of varying size, under a fixed time limit. If an instance is solved within the time limit, its actual runtime is shown. If not, the point is plotted above the time limit on a transformed y-axis that now displays the optimality gap instead of runtime.

An example of such a plot is shown below. Since aggregating this data into a line plot can be challenging, the visualization may become cluttered if too many instances are included or if multiple models are compared simultaneously.

|

|---|

| Split plot illustrating runtime (for solved instances) and optimality gap (for unsolved instances). The y-axis is divided into two regions: one showing actual runtimes for instances solved within the time limit, and one showing optimality gaps for instances where the time limit was exceeded. |

For many problems, there is no single instance size metric to compare over. Usually, you can still classify the instances into size categories. However, for especially complex problems, it may be best to just provide a table with the results for the largest instances to give an idea of the model’s scalability. |

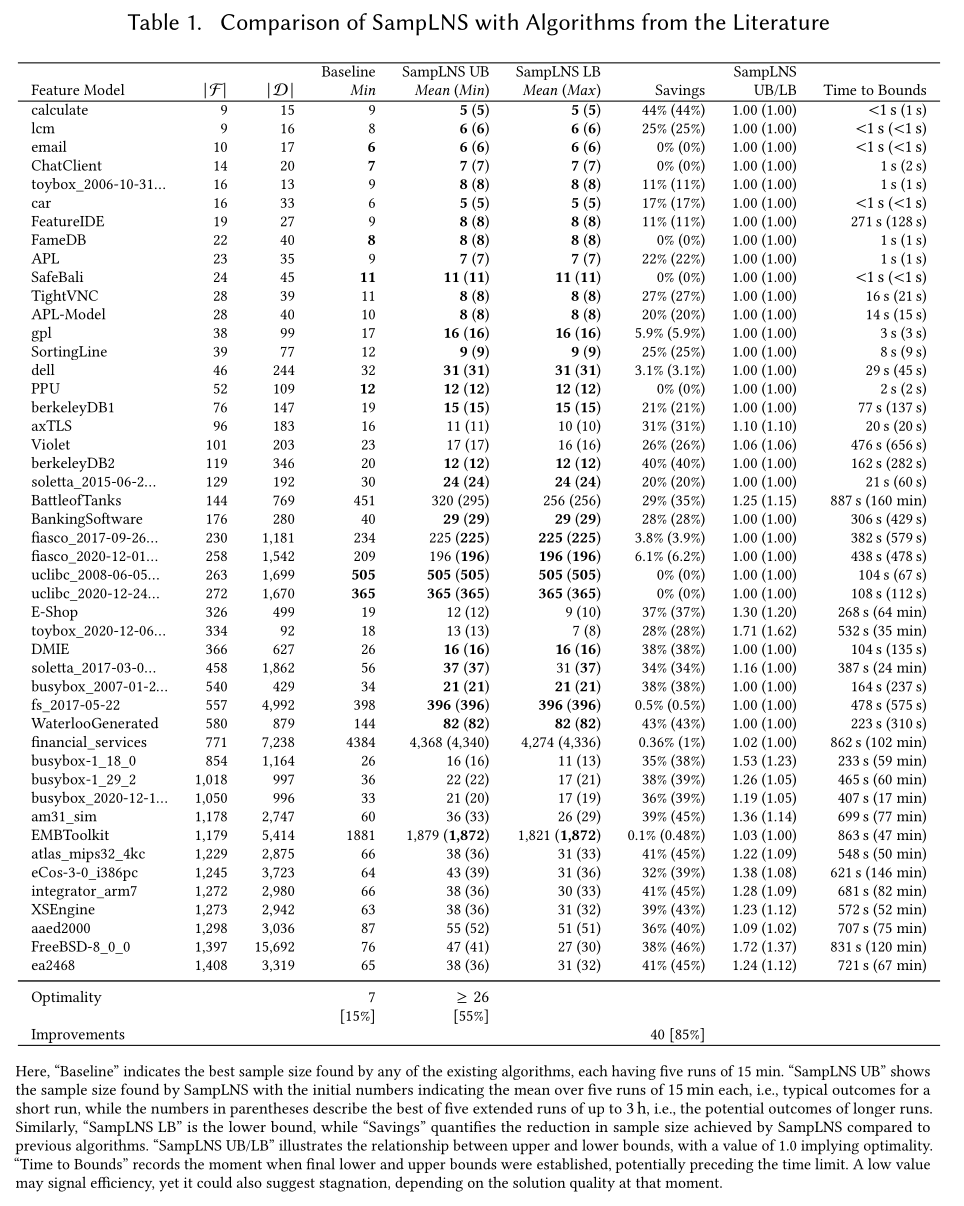

Importance of Including Tables

Tables offer a concise and detailed view of benchmarking results. They allow readers to verify the accuracy of reported data, inspect individual instances, and complement high-level visual summaries such as plots.

While the previous sections presented insightful plots for visualizing performance trends, it is essential to also include at least one table that contains the raw results for the key benchmark instances. Many high-quality papers rely solely on tables to present their results, as they provide transparency and precision.

However, avoid including every table with all available data—this applies even to appendices. Instead, consider what information a critical reader would need to verify that your plots are not misleading. Focus on presenting the most relevant and interpretable results. A comprehensive dataset can always be linked in an external repository, but the tables within your paper should remain clear, selective, and to the point. Even if you are only optimizing for yourself, use plots to gain an overview but also check out the data tables.

|

|---|

| Example table from a recent publication, presenting detailed results of a new algorithm across benchmark instances. While less intuitive than plots, such tables enable readers to examine individual outcomes in detail. |

Distinguishing Exploratory and Workhorse Studies in Benchmarking

Before diving into comprehensive benchmarking for scientific publications, it is essential to conduct preliminary investigations to assess your model’s capabilities and identify any foundational issues. This phase, known as exploratory studies, is crucial for establishing the basis for more detailed benchmarking, subsequently termed as workhorse studies. These latter studies aim to provide reliable answers to specific research questions and are often the core of academic publications. It is important to explicitly differentiate between these two study types and maintain their distinct purposes: exploratory studies for initial understanding and flexibility, and workhorse studies for rigorous, reproducible research.

For a comprehensive exploration of benchmarking, I highly recommend Catherine C. McGeoch’s book, “A Guide to Experimental Algorithmics”, which offers an in-depth discussion on this topic. |

Exploratory Studies: Foundation Building

Exploratory studies serve as a first step toward understanding both your model and the problem it aims to solve. This phase is focused on building intuition and identifying key characteristics before committing to formal benchmarking.

- Objective: The goal at this stage is to gain early insights — not to draw definitive conclusions. Exploratory studies help identify realistic instance sizes, anticipate potential challenges, and narrow down hyperparameter search spaces.

Avoid setting up elaborate benchmarking frameworks during this phase. Keep the process lightweight and flexible to enable rapid iteration. If updating your benchmarks becomes cumbersome each time you adjust your model, it will slow your progress and — since benchmarking code tends to be tedious — you may lose motivation quickly.

From personal experience, I observed a significant drop in productivity when I first learned to build robust benchmarking setups. I began applying the same level of rigor to exploratory phases, mistakenly treating the setup as a one-off investment that would pay off in the long run. However, whenever you do something genuinely interesting, unexpected issues inevitably arise, requiring further iterations on the setup. In trying to anticipate such surprises, it becomes tempting to over-engineer the process—spending excessive time considering what could go wrong and preparing for every contingency, rather than simply getting started.

Instead, strike a balance: avoid letting things become disorganized, but postpone formal benchmarking until you are ready to share results. For example, I used quick exploratory studies in a single jupyter notebook to estimate appropriate instance sizes for the benchmark plots shown earlier. Not a reliable part of a pipeline, but it got the job done quickly and only then I set up a proper pipeline to create my final plots and tables.

Workhorse Studies: Conducting In-depth Evaluations

Workhorse studies follow the exploratory phase and are characterized by more structured and meticulous methodologies. This stage is essential for conducting comprehensive evaluations of your model and collecting substantive data for analysis.

- Objective: These studies aim to answer specific research questions and yield meaningful insights. The approach is methodical, emphasizing clearly defined objectives. Benchmarks should be well-structured and sufficiently large to produce statistically significant results.

While you can convert one of your exploratory studies into a workhorse study, I strongly recommend starting the data collection process from scratch. Make it as difficult as possible for outdated or flawed data to enter your benchmarking setup.

Your exploratory studies should already have provided a reasonable estimate of the required runtime for benchmarks. Always ensure that you allocate sufficient time for potential failures and that your setup can resume if, for instance, a colleague inadvertently terminates your job. Monitor the results while the benchmarks are running—you do not want to wait a week only to discover that you forgot to save the solutions.

I personally structure a workhorse study as follows:

-

Hypothesis or Research Question Clearly define a hypothesis or research question that emerged during the exploratory phase.

-

Experiment Design Develop a detailed experimental plan, including the instance set, the models/configurations to be evaluated, and the metrics to be collected.

-

Benchmark Setup Implement a robust benchmarking framework that supports reproducibility and efficient execution.

-

Data Collection Execute the experiments, ensuring that all relevant data is collected and stored in a structured and reliable format.

-

Data Analysis Analyze the results using appropriate statistical and visualization techniques.

-

Discussion of Findings Interpret the results and discuss their implications in the context of the initial hypothesis or research question.

-

Threats to Validity Reflect on potential threats to the validity of your findings, such as biases in instance selection, model assumptions, or evaluation procedures.

Selecting a Benchmark Instance Set

Constructing a benchmark instance set is often more challenging than it first appears, especially when no established benchmarks exist. Even when such sets exist, they may be poorly sized or less realistic than anticipated. In fact, some seemingly realistic datasets may have had portions of the original data replaced with uniformly random values to preserve confidentiality, often without realizing that such modifications can substantially alter the problem’s characteristics. Crafting a high-quality benchmark instance set can be an art in itself. A notable example is the MIPLIB collection, which stands as a scientific contribution in its own right.

If you already have a deployed implementation, the process is fortunately quite straightforward. You can collect the instances that have been solved in the past and use them (or a representative subset) as your benchmark set. Performing basic data analysis to examine the distribution of instance characteristics is advisable; for example, it may turn out that 99% of the instances are trivial, while the remaining 1% are significantly more challenging and thus more relevant for improvement. In most cases, basic domain knowledge and judgment are often sufficient to construct a useful benchmark set without the need for particularly creative solutions.

If you are not in this fortunate position, the first step is to check whether any public data is available for your problem or for a sufficiently similar one. For instance, although the widely used TSPLIB benchmark set for the Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP) contains only distance information, it is relatively straightforward to generate Capacitated Vehicle Routing Problem (CVRP) instances from it, allowing the reuse of well-structured and challenging inputs for a related problem. This can be done by randomly selecting a depot and assigning a vehicle capacity based on a fraction of a heuristic TSP solution. If you obtain readily available instances, be sure to verify whether they remain challenging; they may originate from a different era or may not have been well-designed, as not everything published online is of high quality (although I hope that this Primer is).

If no suitable public benchmarks are available, you will need to generate your own instances. Even with public benchmarks available, generating your own instances can still be beneficial to generate additional instances in order to control specific parameters and systematically evaluate the impact of varying a single factor on your model’s performance. In typical benchmark sets, the diverse instances can confound the effects of individual parameters, making it difficult to isolate their impact without large datasets and careful statistical design. Nevertheless, it is important to maintain diversity within your general instance set to ensure that your model remains robust and capable of handling a broad range of scenarios.

|

To deepen your understanding of benchmark instance diversity, consider the concept of Instance Space Analysis. Kate Smith-Miles offers an insightful 30-minute talk on this topic, exploring how analyzing the space of instances can guide better instance selection and generation.  |

When implementing your own instance generation, it is often possible to leverage existing tools. For example, NetworkX provides a comprehensive collection of random graph generators that can be adapted to suit a variety of problem settings. An exploratory study is usually necessary to identify which generator aligns best with the requirements of your specific problem. For generating other types of values, you can experiment with different random distributions. One particularly effective technique is using images to define spatial or value distributions, for example, treating pixel intensities as sampling probabilities.

It is also advisable not to combine all your instances into a single set, but instead to evaluate performance separately across different benchmark groups. This approach often reveals interesting and meaningful performance differences. |

A final point worth emphasizing is the importance of generating and storing proper instance files, rather than relying solely on the seed of a pseudo-random number generator. This is a recurring concern I have encountered with both experienced peers and students. While pseudo-random generators are valuable for introducing randomized but reproducible elements into algorithms, they are not a substitute for persistently stored data. (That said, I have seen too many cases where a student unknowingly computed the mean over multiple runs using the same seed.) Although, in theory, a seed combined with the source code should suffice to reproduce a complete experiment, in practice, code tends to degrade more quickly than data. This is especially true for C++ code, which may be less reproducible than anticipated due to subtle instances of undefined behavior, even among experienced programmers.

Efficiently Managing Your Benchmarks

Benchmark data management can quickly become complex, especially when managing multiple experiments and research questions simultaneously. The following strategies can help maintain an organized workflow and ensure that your results remain reliable:

-

Folder Structure: Maintain a clear and consistent folder hierarchy for your experiments. A typical setup includes a top-level

evaluationsdirectory with descriptive subfolders for each experiment. For example:evaluations ├── tsp │ ├── 2023-11-18_random_euclidean │ │ ├── PRIVATE_DATA │ │ │ ├── ... all data for debugging and internal use │ │ ├── PUBLIC_DATA │ │ │ ├── ... curated data intended for sharing │ │ ├── _utils # optional │ │ │ ├── ... shared utility functions to keep top level clean │ │ ├── README.md # Brief description of the experiment │ │ ├── 00_generate_instances.py │ │ ├── 01_run_experiments.py │ │ ├── ... │ ├── 2023-11-18_tsplib │ │ ├── PRIVATE_DATA │ │ │ ├── ... debugging data │ │ ├── PUBLIC_DATA │ │ │ ├── ... selected shareable data │ │ ├── README.md │ │ ├── 01_run_experiments.py │ │ ├── ... -

Documentation: It is easy to forget why or when a particular experiment was conducted. Always include a brief

README.mdfile with essential notes. This document does not need to be polished initially, but it should capture the core context. The more important the experiment, the more beneficial it is to revisit and enhance the documentation once the experiment is underway and you have had time to reflect on its purpose and outcomes. -

Redundancy: Excessive concern about redundancy in your data and code is generally unnecessary. Evaluation setups are not production systems and are not expected to be maintained over the long term. In fact, redundancy, particularly in utility functions, can simplify refactoring. Legacy experiments can continue using older versions of the code, and updates can be applied selectively. It is advisable to include a brief changelog in each utility file to indicate the version in use. Consider this a lightweight form of dependency management. Although copying and pasting code may feel inappropriate to a software engineer trained in best practices, this portion of your work is typically intended to be static for reproducibility, rather than actively maintained.

-

Extensive Private and Simple Public Data: Organize your data into two sections: one for private use and one for public dissemination. The private section should contain all raw and intermediate data to facilitate future investigations into anomalies or unexpected behavior. The public section should be concise, curated, and optimized for analysis and sharing. If the private data grows too large, consider transferring it to external storage and leaving a reference or note indicating its location, ideally with the hope that it will not be needed again. If your experiments are not huge, you may also be able to store all data in the public section.

-

Experiment Flexibility: Design experiments to be both interruptible and extensible. This allows long-running studies to be paused and resumed, and new models or configurations to be added without restarting the entire process. Such flexibility is particularly valuable in exploratory research, which often involves frequent iterations, as well as in large-scale, long-duration runs. The longer an experiment runs, the more likely it is that it will be interrupted by system updates, network failures, or other unforeseen events.

-

Parallelization: Obtaining results quickly can help maintain momentum and focus. Learn to utilize a computing cluster or cloud infrastructure to parallelize experiments. Although there is an initial learning curve, the effort required to implement parallelization is usually small in comparison to the efficiency gains it provides.

Because existing tools did not fully satisfy my requirements, I developed AlgBench to manage benchmarking results and Slurminade to simplify experiment distribution on computing clusters through a decorator-based interface. However, more effective solutions may now be available, particularly from the machine learning community. If you are aware of tools you find useful, I would be very interested in hearing about them and would be glad to explore their potential. |

The CP-SAT Primer is maintained by Dominik Krupke at the Algorithms Division, TU Braunschweig, and is licensed under the CC BY 4.0 license. Contributions are welcome.

If you find the primer helpful, consider leaving a ⭐ on GitHub (574⭐) or sharing your feedback/experience. Your support helps improve and sustain this free resource.